Since a long time, the labour and craft of Muslim workers in Hyderabad, who make edible silver foils, have been repeatedly called into question for being adulterated and unholy in comparison with automation processes with religious discrimination.

Silver-leaf or Waraq workers in Hyderabad have always taken immense pride in their work because of its role in blurring the religious divide. There was a time when they used to travel across states to adorn idols in silver and gold at renowned Hindu temples in Tirupati, the Parthasarthy temple in Chennai and the Golden Car of Arulmigu Subramaniya Swamy Thirukoil in Coimbatore.

Silver-leaf or Waraq workers in Hyderabad have always taken immense pride in their work because of its role in blurring the religious divide. There was a time when they used to travel across states to adorn idols in silver and gold at renowned Hindu temples in Tirupati, the Parthasarthy temple in Chennai and the Golden Car of Arulmigu Subramaniya Swamy Thirukoil in Coimbatore.

But the increasing polarisation and social exclusion in the society has found the Muslim artisans investing their time and labour in a profession that is yielding very poor returns for them. While these workers continue to believe in communal unity, circumstances around them have changed drastically. In the last decade, their labour and craft have been repeatedly called into question for being adulterated and unholy.

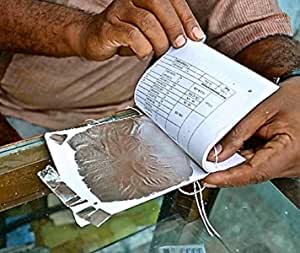

Waraq is the flimsy edible silver and occasionally gold embellishment you find on sweets. The thin silver leaves are also an important component of unani medicine and have been used by unani practitioners for hundreds of years. Gold waraq is used to decorate temple walls, especially around the idols. But these days the artisans’ religion has resulted in social exclusion, inescapable drudgery, poverty and mechanisation. Waraq has been declared a dying craft. “We are not associated with our hard work, but with meat. People prefer machines over us,” says a worker at Intenhad Waraq shop, Charminar.

Waraq rejected because it is being made by Muslims

In recent years, people have been rejecting waraq made by workers. “We have been making waraq for temples and the holy prasad for years, but we are not allowed to anymore. Around seven years ago, reporters would come and observe our work. Then they would ask questions, and tag our products as dirty. They were questioning the leather we use. They wanted to know what animal skin the leather was made from.

In recent years, people have been rejecting waraq made by workers. “We have been making waraq for temples and the holy prasad for years, but we are not allowed to anymore. Around seven years ago, reporters would come and observe our work. Then they would ask questions, and tag our products as dirty. They were questioning the leather we use. They wanted to know what animal skin the leather was made from.

There is a new culture of products made ‘without skin touch.’ Machines have gained more importance, seemingly because of the ‘cow meat’ rumours. This is actually not because of COVID-19. This is because of cow meat. This has become a trend,” says Mohammad Akbar, another worker at the same shop. Akbar explains, “This process does not involve any skin contact in actuality, there are layers of papers and leather in between. But because the workers are Muslim, people associate the product with cow meat and refuse to buy waraq made by us.” He is referring to the process of beating the silver ribbons placed between the papers of a leather-covered book, with a hammer to get the desired thickness.

Afroz Khan, a worker at Metro Waraq shop does not believe in the religious divide. “We don’t understand Hindu-Muslim politics. We depend on each other. For example, our waraq is distributed in all parts of the city and mostly sold to Hindu sweet shops. We also depend on Hindu workers for products that are used in our shop. Even if we are not sitting together and working, we are connected. This is true. Religious divide seems absurd to us. Our waraq has always been distributed by temples as prasad,” Afroz explains.

Automation taking away jobs

Both big and small sweet shops now prefer machines for the silver foils to be placed on the sweets. This has automatically led to a decline in the number of shops employing people for waraq work. Wages have also not improved over the years, and many of the workers know little else to sustain livelihoods.

Both big and small sweet shops now prefer machines for the silver foils to be placed on the sweets. This has automatically led to a decline in the number of shops employing people for waraq work. Wages have also not improved over the years, and many of the workers know little else to sustain livelihoods.

Like many of them, Afroz himself has been working with waraq since he was 16 years old. “Some waraq labourers have been working for 40-60 years. There are no fixed timings. We earn according to our work, so the more we work the more we earn.” There are also no fixed wages for the workers. Eight to twelve hours of work pays them about Rs 600. “This work involves heavy labour and what we earn does not suffice to feed our families.

There is no retirement or escape, which is why very old men keep working to earn whatever amount they can. I cannot leave this work because I don’t know anything else. I have been doing this for the past 20 years,” he says. The situation was even more dire during the pandemic, when everything was closed. The workers were entirely at the mercy of their owners. If the owner was kind enough, he would pay a regular worker something occasionally. Otherwise, the workers were completely unemployed and penniless.

Poor wages discouraging younger generation

It is because of the nature of this hard and dwindling endeavour that youngsters do not want to work in such conditions. There is no hope for an increase in wages either. None of the shop owners have accommodated the idea of a wage hike, and workers are often unable to get more wages even if business is good. About 25 years ago, workers in the area attempted to form a union.

It is because of the nature of this hard and dwindling endeavour that youngsters do not want to work in such conditions. There is no hope for an increase in wages either. None of the shop owners have accommodated the idea of a wage hike, and workers are often unable to get more wages even if business is good. About 25 years ago, workers in the area attempted to form a union.

“Workers of all waraq shops in this area came together and demanded fair wages. They tried to unionise. However, the owners got together and prevented this attempt,” Afroz says, and adds that though there is an urgent need to unionise even to this day, there is no unity among workers to make that happen.

The waraq workers in Charminar are now caught in a web of contradictions. Their specialised skill set prevents them from leaving this line of work, but staying back to work in this field means poor wages and severe discrimination. It is ironic that the workers are forced to defend themselves and an unrewarding profession from rampant communalism, which has resulted in their social exclusion.

Even with the present day divisive Hindu-Muslim politics, the workers do not blame their ills only on the current political dispensation. No one can remember the last time any ruling political party prioritised their rights and demands. “We are beyond the reach of politicians and their policies. We are located in a blind spot,” Afroz admits. What pains the workers is that a tradition which has been alive for thousands of years is being rejected in recent years in the name of religion. “Hakeem Luqman built the practice of waraq production. In recent years, people have been rejecting waraq made by workers.

Machines have gained more importance, essentially, because of the cow meat rumours. We have been making waraq for temples and holy prasad for years, but we are not allowed to anymore,” Akbar says. #tohyd #hydnews